As the region prepares for Sound Transit 2 (ST2) investments to come online, several cities are increasing zoning capacity near future light rail stations. In some cases, this wasn’t a hard sell since many light rail stations are going in along freeways where land has typically been dedicated to malls, warehouses, and light industrial use.

One lingering question is whether by focusing our growth near freeways we are jeopardizing the health of the future residents of these shiny new transit-rich neighborhoods. Luckily, we can mitigate the roadway pollution health risks with freeway lids or removing freeway sections entirely. Such a strategy would allow us to make regional growth centers abutting freeway attractive and healthy places to live. Freeway removal tackles the problem at its source, while lids dampen the dispersal of freeway pollutants and the trees and greenery they add can absorb some of the pollution that does escape.

Momentum is starting to build for freeway lids. The advocacy group Lid I-5 won a $48,000 grant to start community outreach and a further $1.5 million from the Washington State Convention Center public benefits package. Tonight, Lid I-5 Collaborative is hosting a design presentation at Optimism Brewing to review early work from seven different teams for freeway lids in Downtown Seattle. Last fall, Lid I-5 also hosted a charrette on I-5 lid designs to reconnect the University District and Wallingford.

Both Downtown and the University District are densely populated near the freeway, meaning lids there would improve the health of tens of thousands of local residents. Moreover, lids (or highway removal) can make room for people to live in the improved neighborhoods using land recovered from freeway infrastructure.

Breathing Freeway Pollution

A recent UCLA study found the pollution spew radius of freeway was at least twice as large as previously thought–1,000 feet rather than 500 feet–and pollution can even travel one mile downwind. The implications of roadway pollution are dire. People living near freeways higher rates of asthma, other chronic respiratory illnesses, heart disease, sudden cardiac deaths, and strokes, as numerous studies have shown. The Los Angeles Times confirmed rates of particulate pollution spikes near freeways in their own analysis and created a map illustrating the impact.

Los Angeles prohibits siting public schools within 500 feet of freeways and Measure S proposed doing the same for housing but extending the prohibition to within 1,000 feet of freeways. Alas, freeways are so prevalent that such a prohibition would affect a significant portion of the city, hindering an already severely constrained city’s ability to grow. Mayor Eric Garcetti’s administration estimated the 1,000-foot rule would cover “more than 10% of land currently zoned for residential construction in the city, from Westwood to Boyle Heights and San Pedro to Sherman Oaks.” Measure S failed.

The ban-the-housing approach gets it backwards: to protect the public we should seek to eliminate the health hazard rather than the victim. In other words, either we should make freeways less harmful or remove them from our urban areas. That said, we should simultaneously rezone neighborhood interiors to allow dense multifamily housing away from freeway corridors. To do otherwise would be create a deeply inequitable city with lower-income tenants breathing in freeway pollution–unless we mitigate it–while wealthier detached single-family zones are considered off-limits. The added density will allow more frequent transit to serve these formerly exclusively single family areas.

Electric Cars Will Not Save Us

Switching to electric cars may improve our roadway pollution situation but is not a solution in itself. Here’s why:

- Brake pollution or “tire dust” would remain a major source of pollutants.

- Noise pollution will continue negatively impacting humans and wildlife alike.

- Embodied carbon from cars will continue choking the air with greenhouse gases and acidifying the oceans.

Electric cars still require brakes, which are a major source of air pollution. Disintegration of tires, brake pads, and the roadway surface end up dispersing toxic particles into the air. In Pacific Northwest, “tire dust” has also been implicated in coho salmon kills as they end up in area streams and ultimately Puget Sound. Since electric cars are typically heavier than comparable conventional cars because of their large batteries, they require stronger brakes. The benefits of switching away from high-polluting diesel fuel may be outweighed by “wear-particles” from heavier vehicles braking, The Guardian reported:

Increasing amounts of wear-particles have been found in new research from King’s College London. Scientists tracked air pollution alongside 65 roads for ten years. The researchers found some roads where the air pollution benefits from improvements in diesel exhausts were outweighed by increases in particles that come from the wear of tyres, brakes and the road.

So, even though we can hope the Puget Sound region’s fleet of cars and trucks will convert to electric within a few decades, we cannot expect the problem to go away. Autonomous vehicles will not fix wear-particle issue either since robot cars do not dispense with the needs for brakes; even with electric autonomous vehicles, noise pollution will continue to be an unmitigated negative externality of freeways. Plus, whatever fuel they’re consuming, cars represent embodied carbon since their manufacture and distribution puts tons of carbon into the air. The Guardian even suggested the embodied carbon of a car may exceed its total tailpipe emissions. Switching to electric can address the tailpipe emissions problem but not the embodied carbon problem. If private vehicles continue to be our transportation model, we will have a very hard time reducing carbon pollution and mitigating climate change.

Neighborhoods near freeways will continue to be highly polluted unless we do something about it. Removing the freeway, like I’ve proposed for Downtown Seattle is one option. Another is to build freeway lids in highly polluted areas to improve health and quality of life. We should be doing everything we can to encourage mass transit use and remove incentives for private vehicle use. ST2 and ST3 ballot measures showed the region supports going that direction–although some politicians remain convinced cutting the ST3 budget to lower car tab fees is a priority. Adding more high quality transit lines (like the Magenta Line) and implementing a carbon tax and congestion pricing to make motorists pay more of the social cost they are externalizing on the population writ-large and on the planet’s deteriorating ecosystems.

Wilburton and Downtown Bellevue

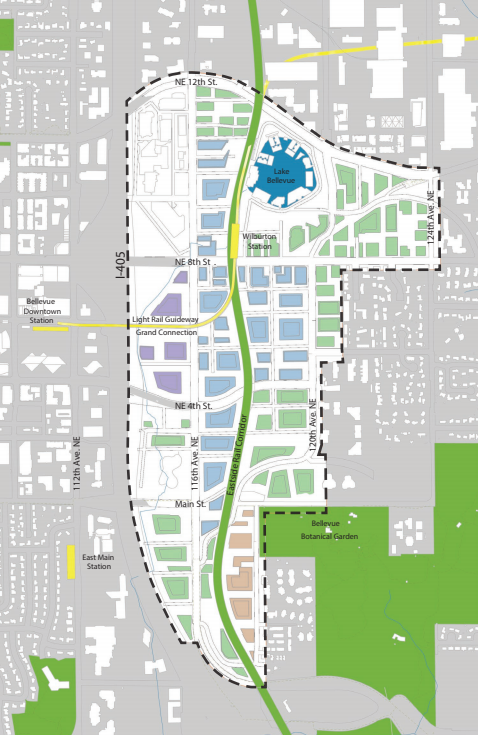

Bellevue is mulling an rezone proposal for the Wilburton neighborhood, which will have a light rail station when East Link opens in 2023, with comments on the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) open until March 19th.

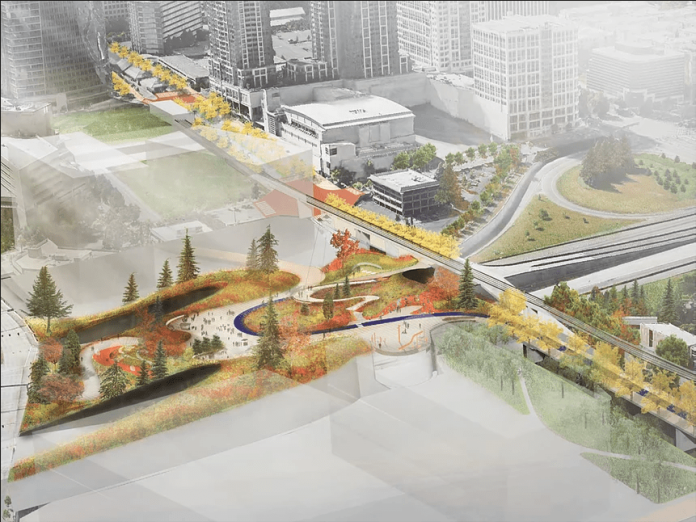

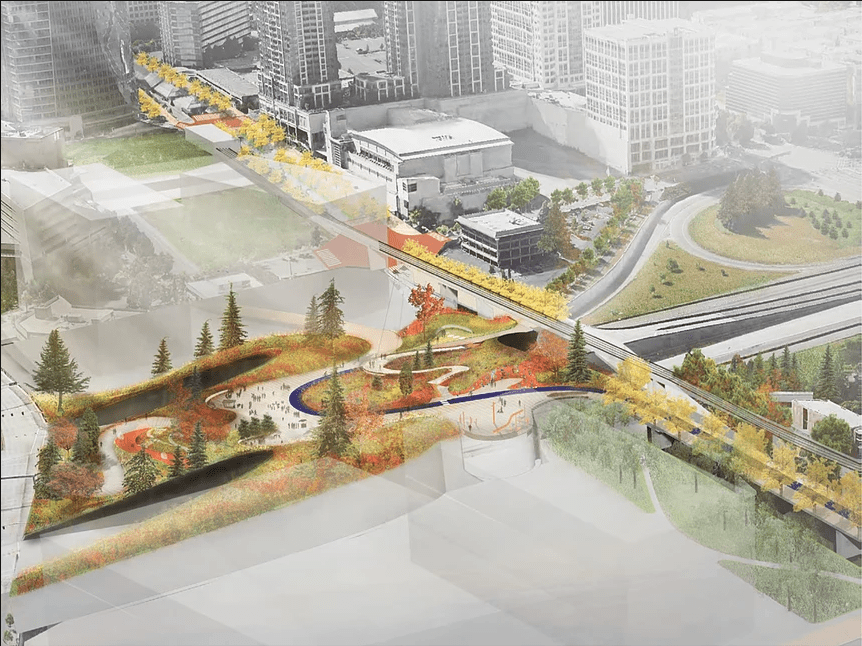

Alternative 2 is especially ambitious with 450-foot towers permitted west of the station and 250-foot buildings east of it. Unfortunately, a good chunk of the rezoned land is within 1,000 feet of I-405. Luckily, the DEIS does explore a small lid over I-405 to increase connectivity. A larger lid would have the benefit of dampening more noise and particulate pollution.

The DEIS studies how the alternatives will combine with “Grand Connections,” an effort to increase Wilburton’s connectivity. Grand Connection Option C includes a proposal for a lid over I-405 which would tie together Wilburton to Downtown Bellevue south of NE 6th St.

Bellevue projects that Alternative 1 would result in 13.1 million square feet of total development by 2035 while Alternative 2 would result in 16.3 million square feet. The no-action alternative would result in 4.2 million square feet. Alternative 1 tops out with building heights of 250 feet rather than Alternative 2’s 450 feet.

Comments on the Wilburton DEIS can be emailed to bcalvert@bellevuewa.gov with the subject line “Wilburton Draft Environmental Impact Statement.” I’d encourage people to support the more ambitious Alternative 2 and ask Bellevue to pair it with the Grand Connection Option C to create an I-405 lid to make the healthiest and most welcoming neighborhood. We should also be studying if it’d be feasible to build a bigger lid considering how much the health of future Bellevue residents is at stake.

Other places that have upzoned, or are in the midst of upzoning near freeways or major highways as light rail or bus rapid transit goes in include:

- Seattle’s Northgate

- Shoreline South (147th St Station)

- Shoreline North (185th St Station)

- Lynnwood City Center

- Downtown Bellevue

- Bellevue’s Spring District

- Redmond’s Marymoor District

- Downtown Redmond

- Kirkland’s Totem Lake

- Kenmore and Bothell along SR-522 BRT.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.